In the dense jungles of ancient Mesoamerica, where the hum of insects blended with the whispers of priests, one deity occupied a uniquely sweet space in the spiritual landscape: the Maya Bee God. This enigmatic figure, often depicted with translucent wings and a belly dripping golden honey, represented far more than a simple agricultural symbol. For the Maya civilization, bees were sacred messengers between worlds, and their divine patron held the keys to life, death, and the afterlife’s floral paradise.

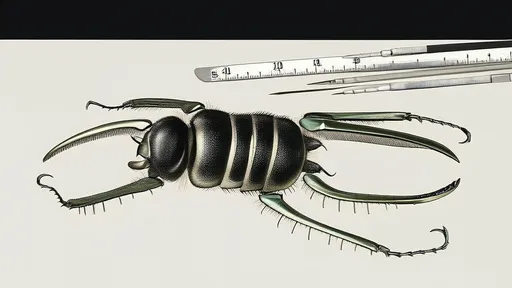

The Maya Bee God, known as Ah-Muzen-Cab in some codices, wasn’t merely a passive symbol of nature’s abundance. Archaeological evidence from temple murals and ceramic vessels reveals a deity deeply woven into royal rituals and cosmic mythology. Unlike European apiary traditions that later reduced bees to utilitarian pollinators, the Maya saw their hives as miniature temples. Stingless bees (Melipona beecheii), native to the Yucatán Peninsula, produced honey so precious it served as both currency and sacrament—a duality reflected in the Bee God’s dual role as both provider and psychopomp.

Recent excavations at the ruins of Nakum in Guatemala uncovered a 1,200-year-old stingless beehive crafted from limestone and adorned with glyphs praising the Bee God’s role in sustaining the "blood of the earth"—their poetic term for honey. This discovery confirmed what anthropologists long suspected: Maya beekeeping wasn’t just an economic activity but a form of worship. Priests dressed as the Bee God during equinox ceremonies, their ritual dances mimicking the insects’ zigzag flight patterns to channel divine energy into the honey harvest.

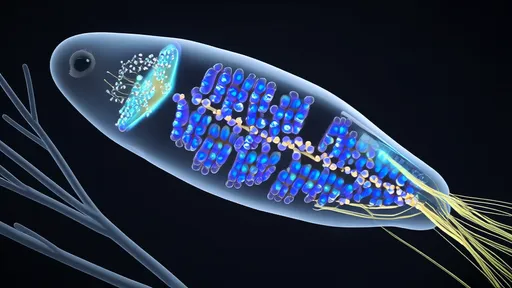

The Dresden Codex, one of only four surviving pre-Columbian Maya books, contains startling astronomical references to the Bee God’s celestial counterpart. On page 24, a sequence of glyphs describes Venus transforming into a swarm of bees during its inferior conjunction—a phenomenon that signaled the start of the honey-gathering season. This fusion of astronomy and apiculture underscores how the Maya perceived no boundary between science and spirituality. Their beekeepers doubled as astronomers, tracking planetary movements to determine optimal harvest times.

Spanish chronicler Diego de Landa’s 16th-century accounts, though biased by colonial prejudice, inadvertently preserved crucial details about the Bee God’s darker aspects. In his Relación de las cosas de Yucatán, he describes indigenous rituals where honey was mixed with hallucinogenic bark extracts and consumed during visions of the Xibalba (the Maya underworld). Shamans reported encountering the Bee God there, not as a benevolent figure but as a gatekeeper who decided which souls could access the honey-filled paradise of the afterlife. This duality—nurturer and judge—echoes the Maya’s complex understanding of nature’s gifts as both blessing and responsibility.

Modern Lacandon Maya in Chiapas still whisper prayers to K’ayum, a surviving iteration of the Bee God, before harvesting wild honey. Their traditional log hives, called jobones, are always positioned facing cardinal directions to honor the deity’s cosmic connections. Ethnobotanists working with Lacandon elders have documented over 37 species of nectar-bearing plants considered sacred because they "feed the gods’ bees." This living tradition offers rare insight into how pre-Columbian apiculture might have functioned as a complete theological system.

The Bee God’s symbolism extended into Maya warfare and politics. When the ruler of Tikal commissioned a series of stelae commemorating his victory over Calakmul in 562 CE, artisans carved the triumphant king wearing a headdress of crystallized honeycomb—a clear nod to the Bee God’s patronage of conquest. Honey’s preservative qualities made it a metaphor for eternal power, while its flammability (used in incendiary arrows) tied it to destruction. This paradox captures the Maya worldview where creation and devastation were inseparable halves of existence.

Contemporary interest in ancient Maya beekeeping has taken an urgent turn with the global decline of bee populations. Genetic studies of surviving Melipona beecheii colonies reveal traits developed through centuries of selective breeding by Maya priests—traits that could help modern bees survive climate change. Perhaps the most poignant legacy of the Bee God is this: a 3,000-year-old spiritual tradition that might hold scientific solutions for our ecological crisis. As researchers decode glyphs about "speaking to bees," they’re discovering the Maya may have practiced advanced vibrational communication methods now being explored in biodynamic agriculture.

From the stepped pyramids where honey was offered to the gods, to the modern kitchens where Yucatecan cooks still use ancestral recipes for honey-infused balché wine, the Bee God’s presence endures. This isn’t just a story about an ancient deity; it’s a testament to how civilizations can find divinity in the smallest, busiest corners of the natural world—and perhaps a reminder that we might need to rediscover that wisdom ourselves.

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025

By /Jul 7, 2025